The literary world was shocked this month to learn the story of Andrea Robin Skinner. How, as a child, she was indecently assaulted by her stepfather, Gerald Fremlin, and he told her to keep quiet about it, to not tell her famous mother, the prize-winning author Alice Munro.

Skinner didn’t stay silent, but one of this country’s most celebrated authors rejected her own daughter in favour of her abuser.

But one key question remains on the minds of Munro’s fans, others who have been abused and scores of journalists: How could this stay a secret for so long?

The Star explores that question, backed by interviews with Andrea Skinner and her family; Skinner’s letters to her mother’s biographer, who deemed the abuse a “family matter” not worth mentioning; and the recollections of the Crown attorney who prosecuted her stepfather.

In the shadow of my mother, a literary icon, my family and I have hidden a secret for decades. It’s time to tell my story.

The family secret

In 1976, Gerry Fremlin — then in his 50s — sexually assaulted his stepdaughter in the home he shared with her mother.

It was the house in Huron County where Gerry had grown up: a big white Victorian wood-clad cottage with old maple trees in the yard and farm fields behind — about 35 kilometres from Munro’s hometown of Wingham, which made appearances in her stories as a place called Jubilee.

Despite her stepdad’s threat to stay silent, Andrea told one other person about the abuse: her stepbrother, Andrew Sabiston, who insisted she tell his own mother, Carole Sabiston. She, in turn, told her new husband, Andrea’s father.

In a decision that is common in cases of family abuse, Jim Munro did not confront Gerry or his ex-wife Alice with his daughter’s account, nor did he alert police — it would be decades before the law became involved.

Andrew Sabiston says the silence started when as a boy he found about the abuse by Alice Munro’s husband. “I thought, everything would be OK. Our

Jim Munro died in 2016, so we can no longer ask him why he chose silence, but Carole — Jim’s second wife, after Alice — remembered his decision. “I’ve been haunted by this forever … and that I was so naïve and didn’t know what to do,” she told the Star.

Sabiston recalled telling Jim he had to phone Alice and tell her. He responded, about his daughter, “Well, I don’t know that she’s really telling the truth.”

“That was a common attitude,” Sabiston said.

She described pacing the floor for “an entire day”; she kept going to the phone, feeling she should tell Alice, even if Jim didn’t. “I couldn’t do it because I was forbidden … it just haunts me that I respected his authority as a father.”

She added: “We didn’t do it in our family and, of course, now we’re wondering, ‘Why didn’t we?’ We couldn’t.”

Alice’s other children, Sheila, 20 at the time, and Jenny, 16, weren’t told the whole story and were tasked with secrecy; for stepbrother Andrew, the silence from the adults told him everything had been taken care of.

For Andrea, the silence said she was on her own.

“I needed to belong in my family. And I learned what gave me belonging, and what made me feel excluded and cast out,” she told the Star. “I learned very early on that showing pain was not OK. I played along.”

A mother’s reaction

Years later, now age 25, Andrea decided to take control of her story.

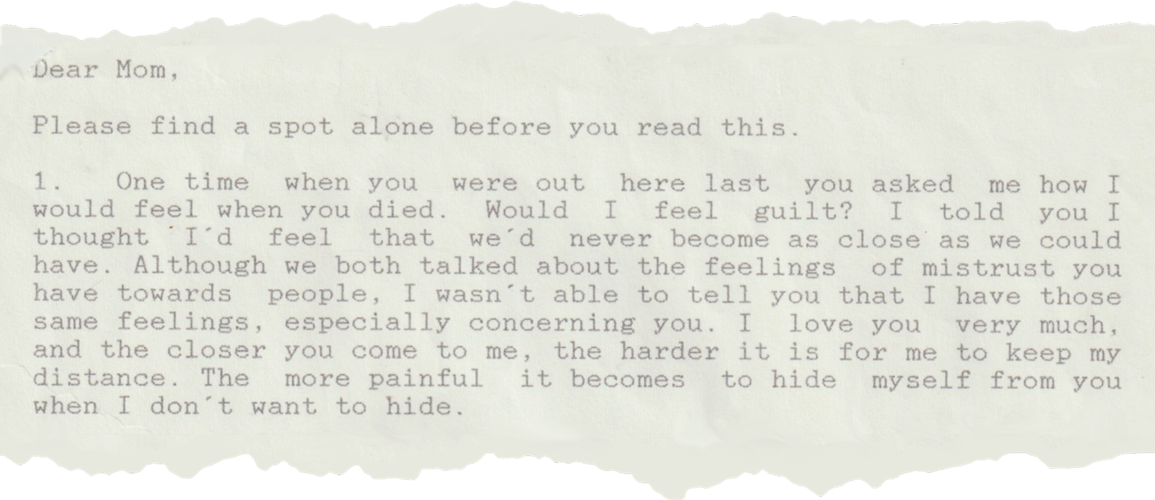

In 1992, she wrote a letter detailing the abuse and sent it to her mother — now a towering figure in Canadian literature, beloved for her short stories exploring the lives of girls and women and the internal world they experienced under the surface of mostly small-town life.

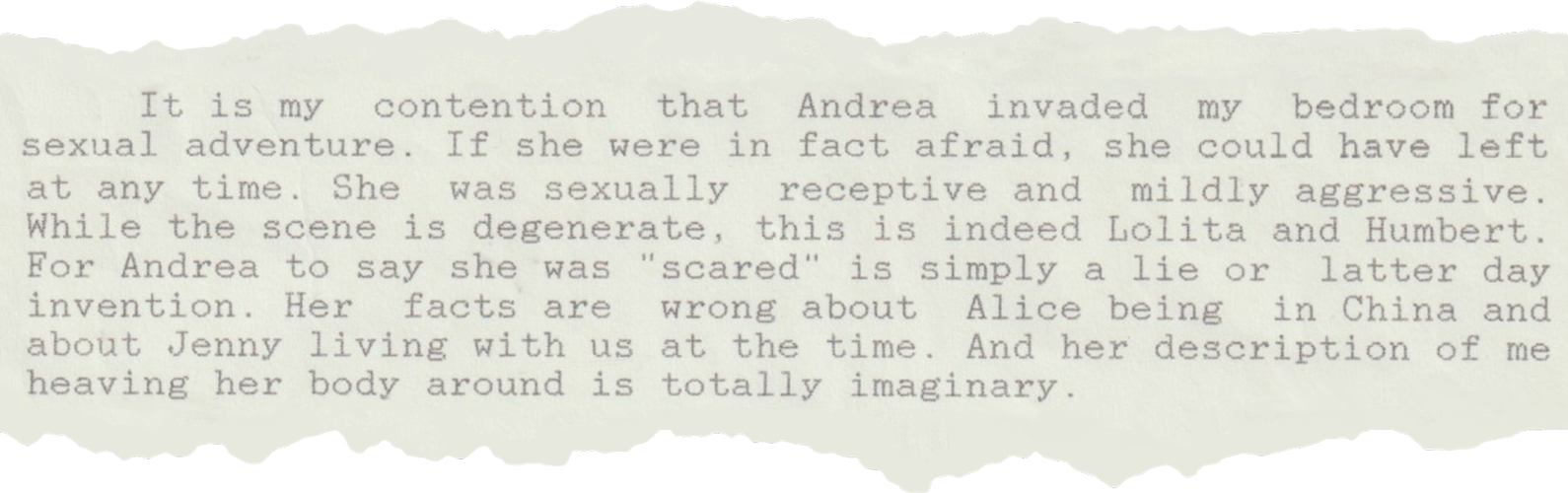

An excerpt from Andrea’s letter to her mother.

The secret was finally revealed, but Alice rejected her daughter’s experience.

In response to Andrea’s letter, Fremlin wrote a series of his own, sending them to Jim Munro and Carole, detailing his view of what had happened. In them, he admitted to sexual touching but claimed Andrea — nine — had initiated it, calling her a “Lolita” as in the Vladimir Nabokov novel of the same name and himself a “Humbert Humbert.”

An excerpt from Gerry Fremlin’s response to Andrea’s letter to her mother.

An excerpt from Gerry Fremlin’s response to Andrea’s letter to her mother.

After a few months of separation, Munro returned to her husband.

The family’s life continued more or less as usual, a life from which Andrea had mostly retreated. When she was 33, Andrea got married, and had twins at age 36. In 2004, Andrea decided to go to the police.

She handed over the letters; when an OPP investigator confronted the now-80-year-old Gerry and Alice, the author responded angrily. She told the officer Andrea was lying and called her names.

But the letters were irrefutable and, in 2005, Fremlin pleaded guilty to indecent assault in an Ontario courtroom. Andrea was elated. She finally had something “recorded in a criminal context that could be referred to by me or anyone.”

After 30 years of secrecy, her stepfather’s actions were on the record. The justice system had worked.

What never made the books

“I couldn’t wrap my head around her attitude,” retired OPP detective Sam Lazarevich told the Star of meeting celebrated author Alice Munro in 2004.

The conviction provided Andrea with — she hoped — the proof she needed for people to finally listen.

After the conviction in 2005, she sent a pair of letters to Bob Thacker, the author of her mother’s biography “Alice Munro, Writing Her Lives,” first published that year and updated in 2011.

In them, she alerted Thacker to the abuse, asking that he include the “truth” of Gerry in the biography.

“Any mention of Gerald Fremlin, unless it’s a listing in a phone book, that doesn’t mention he is a pedophile, is extremely objectionable,” Andrea wrote in a letter dated July 4, 2005. “It is mind-boggling to me that you don’t see the information Jenny and I have given you as key to your work.”

The biography is described by publisher McClelland & Stewart as showing how Alice Munro’s “life and her stories intertwine.” Thacker steeped “himself in Alice Munro’s life and work, working with her co-operation to make it complete,” the publisher’s description says.

Andrea’s abuse is not mentioned, nor is Alice’s reaction.

Thacker, who still has the letter in his files, but not his response, said in an interview with the Star he “fully expected this to come to light after Alice died.”

In fact, he had spoken with Alice about it in 2008, when he was interviewing her for a potential update, he told the Star. “She asked me to turn off the recorder and she wanted to talk about it. And we did. It was a horrible thing to learn about and it was a horrible thing to know about.”

But he didn’t believe this new information changed the thrust of his book. “I saw it as a family matter,” he said.

“It was a decision I made and it’s the decision I stand by today … I was dealing primarily with my principal and her texts,” he told the Star. “One of my reviewers when it was published chided me that it wasn’t much of a biography, that it was really the history of Alice Munro’s texts. That’s what I wanted to do.”

It wasn’t the only book to avoid the family secret.

In 2001, Sheila Munro became the second woman in the Munro family to publish a book: her memoir, titled “Lives of Mothers and Daughters: Growing Up With Alice Munro.”

Sheila worked on the book with Doug Gibson, Alice’s longtime editor and publisher since 1974.

“The story I was writing was about the evolution of a writer,” Sheila told the Star. She wanted to end the book when she reached 21 – when her adult life began. “I felt that the more interesting parts of my story were growing up with her and her childhood ... her mother having Parkinson’s ... and the ancestors.”

It also “would have avoided the problem of how to write about the abuse,” she said, which she also felt was Andrea’s story to tell.

She didn’t tell Gibson about the abuse while she was writing the book, and doesn’t know whether he knew but, in 2002, as the book was launching, she told him the secret.

Approached by the Star, Gibson said: “As Alice Munro’s Canadian editor and publisher, I was aware that Alice and Andrea were estranged for a number of years. In 2005 it became clear what the issue was, with Gerry Fremlin’s full shameful role revealed, but I have nothing to add to this tragic family story and have no further comment to make and hope that this helps the family to recover.”

He added: “With respect to your inquiry about Sheila’s book, it was published in 2001 before the court case, which as stated above made it clear what had happened. Again, I have nothing further to add.”

McClelland and Stewart published both Sheila and Alice’s books as well as Bob Thacker’s. When asked about the relationship and whether they knew about the abuse, the publisher responded in a statement: “We were shocked and deeply saddened to read Andrea Robin Skinner’s story in the Toronto Star on Sunday. As we conveyed directly to Andrea and her siblings, we support and respect Andrea’s bravery in sharing the trauma she has experienced and the steps the family are taking to heal.”

Over the years, others inside the literary community learned, too.

Fellow writer and long-time friend of Munro’s, Margaret Atwood, wrote in an email that she didn’t know about the abuse until Gerry was dead and Alice developed dementia. (Gerry Fremlin died in 2013, at 88).

Alice Munro and Margaret Atwood in 2013, celebrating Munro’s Nobel Prize win.

Sheila MunroShe was shocked; it was not the type of behaviour expected from “the Alice I knew. But obviously I didn’t know her well. However, it’s in the stories and so is that kind of abuse, in ‘Lives of Girls and Women.’ I wonder if a similar thing happened to her?”

Atwood doesn’t know any more than that and didn’t know Alice’s point of view of the family secret — “By the time I found out, she was beyond talking,” Atwood wrote.

She and another friend, the writer Jane Urquhart, visited Alice at different times. In her final years, daughter Jenny was looking after her mother — arranging first for a house and caregivers in Port Hope, and then, in 2021, a spot in a nursing home near Millbrook.

My parents let my sister down. I should have spoken up sooner, writes Alice’s daughter Jenny Munro.

Jenny recalled to the Star: “Both Margaret and Jane visited her, at different times. Each at some point asked me if Andrea was visiting Mom. I told them she had a good reason not to, because she was sexually abused by Gerry, and Mom went back to him after she knew. I don’t think I told them any details and they didn’t ask. They seemed appalled by it.

“It is possible they had heard rumours but I don’t think Mom ever confided in them,” she told the Star.

Writing through a publicist, Jane Urquhart told the Star she had nothing to add.

Why no reporting?

In the years that followed, Andrea continued to send emails to various news outlets, but, she said, no one responded until the Star published her account this month. We don’t know whether any of those reporters actually saw Andrea’s emails.

The 2005 court case, however, was on the record, but was never reported on. The Star cannot know if any journalists were aware of the charges against Gerry Fremlin, but it would not be unusual for such a case to go unreported in one of Ontario’s local courts. Several details of the case also made it more likely to be missed than usual.

For one thing, cases involving child sex abuse victims are handled carefully in Canada’s justice system. The identities of child victims, including any identifying family relationships to their alleged abusers, are treated especially delicately. In 2005, the Goderich, Ont., Superior Court’s docket — the daily schedule of hearings — would not have been posted online, and any local reporter in the courthouse that day most likely would have found the case listed on a paper copy under the initials, “G.F.”

For another, justice came unusually swiftly.

Police laid the charges against Gerry on Dec. 30, 2004, and his case was in court by February 2005. “Usually, the process takes a lot longer,” recalled Bill Morris, speaking to the Star in his law office in Goderich, Ont.

Morris, who was a prosecutor at the time, remembers an early meeting with Fremlin’s defence counsel Paul Ross — a prominent area lawyer who died earlier this year — to discuss possible resolutions.

Recalling the conversation generally, Morris said: “He probably said to me, ‘Well, if he pled guilty what kind of sentence could you live with in these circumstances? Could we have a non-custodial sentence if we put in safeguards?’ ”

Morris said he next would have taken the idea to Andrea, and said, “Here are the options: we could go to trial, you might get more of a stricter sentence, but then you would have to prove the case and in criminal court there is no guarantee how things are going to go.”

Justice John Kennedy approved of the plea agreement on March 11, 2005. Fremlin was handed a suspended sentence and two years probation with conditions not to have contact with Skinner, and not to be in the company of a person under 16 unless accompanied by an adult.

All told, the case was closed in under three months.

Why so fast?

For one, Morris said, the case was taken to Superior Court, where there’s less traffic. A second reason would be the question of “exposure” and “whether you want somehow the media to find out about it.”

He explained: “If the media’s not in court and you deal with it quickly, well then you don’t find out about it.”

He told the Star the defence did not raise the issue to him, but “from my point of view, it didn’t matter. It was a decision basically for the family to make, for (Andrea) to make about how the case should be dealt with. That’s what I suspect was happening — they just wanted to move the case along so it wasn’t in the system very long.”

As it happens, it can be surprisingly easy to keep a secret in a small town.

In Clinton, Ont., where Alice and Gerry lived for many years, nobody knew about the court case that was going on in the nearby town of Goderich; even years later, an extended member of Fremlin’s family told the Star he had no idea about the charge and conviction.

“It’s a public courtroom and for anyone who is there, it’s not a secret,” said Morris. Still, he explained that most often it’s on one of the parties of the case to tell the media, if they want it to be known in public.

That didn’t happen in Fremlin’s case; nobody spoke out.

Speaking to the Star, Andrea said she wanted the case public at the time, but didn’t feel Morris supported her.

Asked about this, Morris said: “I was a Crown attorney for 32 years and I dealt with many, hundreds if not thousands of complainants, and I would never tell anyone not to do something like that, because it’s up to them.”

During his decades in the criminal Justice system, he saw many cases like this, “where many families have hidden secrets and how they deal with them is really dependent on the family.”

He admits he was surprised it took almost two decades for the story to come out, “but it wasn’t up to me to make that call, whatsoever.”

Alice Munro died in May 2024, at 92.

In 2013, when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature, the awards published a biography listing her considerable literary achievements. Among other things, it read: “Alice Munro is married with two daughters from her first marriage.”

Andrea was the unmentioned third.

Correction - July 16, 2024:

This article was updated previous version that referred to Sheila and Jenny as Andrea’s children. In fact, they are Alice’s other children and Andrea’s siblings.