Jean Paul Riopelle is widely considered the greatest Canadian painter of the postwar era and, at the very least, the Canadian painter of widest renown.

In an impressive show, “Jean Paul Riopelle: Visual Exploration,” Corkin Gallery gathers work the artist made between the 1940s and ’90s.

Born in Montreal in 1923, Riopelle came of age under the 20-year premiership of Maurice Duplessis, a time known in Quebec as the Great Darkness for its staunch conservatism. At 19, Riopelle enrolled at the Ècole du Meuble, where he was taught and mentored by the abstract painter Paul-Émile Borduas. Heavily inspired by André Breton, the French founder of Surrealism, Borduas started a group called Les Automatistes.

He invited students such as Riopelle, Marcel Barbeau and Roger Fauteux to paint automatically, “in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or esthetic concerns.” The Automatistes put on group shows and met regularly to discuss the issues of the day. Most pressing of these issues, they thought, was the artistic and cultural repression that stifled the province’s creative potential.

In the late 1940s, Riopelle started squeezing layers of oil paint directly from the tube onto his canvas and, instead of using a brush, spontaneously spreading the paint around with a palette knife.

COURTESY CORKIN GALLERYIn 1948, Borduas drafted a manifesto titled “Refuse Global” (or “Total Refusal”), which Riopelle and his fellow students signed. It radically denounced the influence of the Catholic Church in Quebec and is shot through with the revolutionary hope that soon Quebecois will turn “to glorious anarchy to make the most of their individual gifts.”

The manifesto was widely condemned by the press and Borduas was fired soon after its publication. By this point, Riopelle, who saw in Paris potential for unlimited expression, had settled in that city.

In Paris, Riopelle made the acquaintance of Breton, who was impressed by his work. He invited Riopelle to show at the sixth International Exhibition of Surrealism, which Breton organized with Marcel Duchamp.

On view at the Corkin Gallery are six untitled watercolours that Riopelle displayed at the exhibition. These paintings feature gorgeous clouds of watercolours in pinks and purples, on top of which lacy black ink is spilled seemingly at random. Riopelle would soon take this lush use of colour and automatic method to their extremes, and his attempt to represent movement through the wild snaking of lines would continue throughout his career.

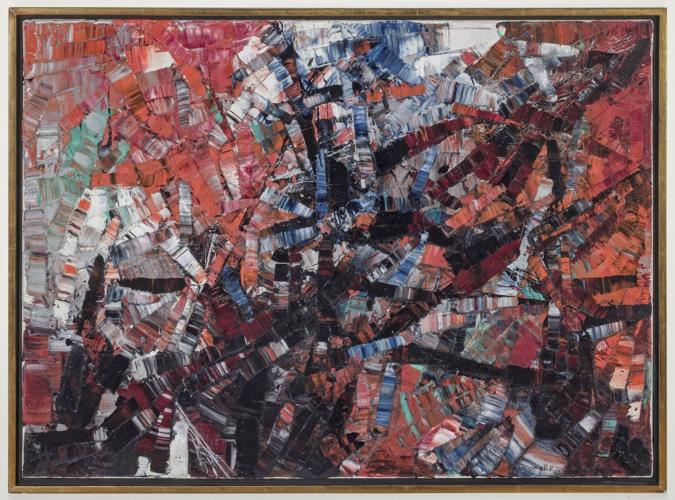

The Paris that Riopelle arrived in was no longer the capital of the art world. That was New York City, where abstract expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning were forging a new painterly language. But, like those artists, Riopelle devised a new way of painting at this time. In the late 1940s, he started squeezing layers of oil paint directly from the tube onto his canvas and, instead of using a brush, spontaneously spreading the paint around with a palette knife.

The strokes that resulted looked like tesserae, small blocks of stone or tile, and the surfaces of the paintings resembled mosaics.

“Couleur (Colour),” 1955, exemplifies Riopelle’s work from this period. The bright reds at the edge of the canvas turn crimson as they approach the middle, until gradually they look like charred black streaks.

COURTESY CORKIN GALLERY“Couleur (Colour),” 1955, which is included in the Corkin show, exemplifies Riopelle’s work from this period. The bright reds at the edge of the canvas turn crimson as they approach the middle, until gradually they look like charred black streaks.

Riopelle uses colour to suggest the appearance of velocity. The tortured palette also gives the work emotional intensity. His knife slices into the canvas, sharpening the edges of his paint and giving the work a three-dimensional quality. The painting invites the viewer to look at it from close or afar, from this side or the other.

In 1955, Riopelle met the American painter Joan Mitchell, another member of the New York School. Their relationship lasted over 20 years, and the work both created in that time possesses a beauty and skill that remains one of the high points of modern painting.

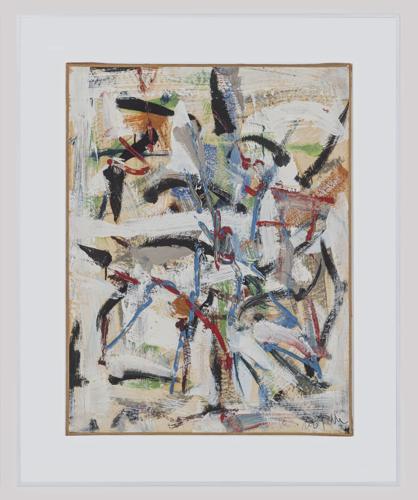

“Sans titre,” 1958, is a highlight of the Corkin Gallery Jean Paul Riopelle show, with the athletic movement of Riopelle’s brush strokes and his exuberant use of colour.

COURTESY CORKIN GALLERYOne can detect Mitchell’s influence in “Sans titre,” 1958, a highlight of the Corkin Gallery show, with the athletic movement of Riopelle’s brush strokes and his exuberant use of colour.

By the late ’60s, Riopelle was spending more time in Quebec and northern Canada. The influence of the landscape and culture is apparent in work from this period.

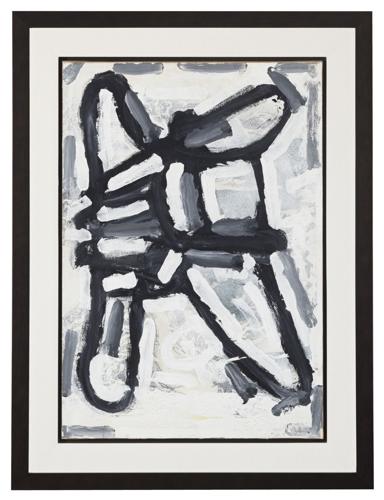

Riopelle was inspired to paint the looping black figure at the centre of “Ficelle En Marche (String Work),” 1972, for example, by ajaraaq, an Inuit string game sometimes referred to as Cat’s Cradle. Its background — acrylic streaks of white over a bright orange — has the luminance of sunlight hitting open fields of snow.

Riopelle was inspired to paint the looping black figure at the centre of “Ficelle En Marche (String Work),” 1972, by ajaraaq, an Inuit string game sometimes referred to as Cat’s Cradle.

COURTESY CORKIN GALLERYRiopelle settled in the Laurentians in 1989 where he had built a studio. When he died in 2002 at the age of 78, he was acknowledged as a painter of firsts: first Canadian to win the UNESCO Prize at the Venice Biennale, first Canadian to sell a painting for over $1 million.

That all seems to fade away in front of his canvases, though, which made good on the “glorious anarchy” he and the Global Refus had predicted all those years before.

“Jean Paul Riopelle: Visual Exploration” is at the Corkin Gallery, 7 Tank House Lane in the Distillery District, until June 30. See corkingallery.com for information.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation