Even among film buffs, production designers are rarely discussed. Their work is often overshadowed, or even attributed to others, like that of cinematographers. A few PDs, such as Rick Carter (“Avatar,” “Jurassic Park”), Bo Welch (“Edward Scissorhands,” “Men in Black”), Dante Ferretti (“Casino,” “Gangs of New York”) and Catherine Martin (“Moulin Rouge,” “Elvis”), have garnered some name recognition.

But perhaps none has accrued more reverence than Jack Fisk, recently Oscar-nominated for “Killers of the Flower Moon.” His work is the subject of a new retrospective, “Grand Design: The World-Building of Jack Fisk,” curated by author, critic and Toronto Star contributor Adam Nayman, beginning Aug. 8 at the TIFF Lightbox.

In a career spanning more than 50 years, Fisk has carved out a special place in cinema, helping some of the greatest directors of all time — Terrence Malick, David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson and Martin Scorsese, among them — craft images that have defined and redefined the look of America in the public imagination.

“They’re seen as having a vision. They’re seen as creating worlds on screen, these realities that people get lost in and return to,” Nayman says, pointing to Fisk as “someone who helps literally build those realities from the ground up.” No wonder, then, that Nayman thinks of Fisk as “a major author of American film.”

Perhaps the most indelible of Fisk’s sets is a tall house in the middle of a wheat field in Malick’s 1978 masterpiece, “Days of Heaven,” designed to express the spectre of Americans’ place in the country’s vast landscape. As art, it’s magnificent, taking inspiration from the American realist paintings of Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth. As a feat of production design, it’s even more impressive. With just six weeks to go before the Hutterite farmers in rural Alberta were set to harvest their uniquely tall wheat, perfect for Malick’s vision of an ocean of golden stalks, Fisk had the house built in just one month, giving the production two weeks to use it.

Unlike most sets, the house in “Days of Heaven” was not mere a façade — as is normal in Hollywood filmmaking — with the interiors shot at a different location or in a studio. Fisk, in all his work, favours 360-degree sets, even when the script might only call for one wall here, and another there.

In one interview, he explained in his unfussy way: “I like the magic of cinema. My magic is that I can usually do stuff cheaper than anyone else by building it real.” The resulting Fisk set allows the director to change things up, shooting from any angle, all while maintaining a grounding in reality.

For Fisk, reality is paramount. Working regularly on period films, he’s a stickler for historical detail. He dives deep into primary sources to unearth the buried and forgotten esthetics of the past, getting specific paint colours just right, the mix of dirt on the ground just so, homing in on odd quirks of architecture and how people actually used the spaces they occupied.

For “There Will Be Blood,” starring Daniel Day-Lewis, Jack Fisk built a replica of a 20th-century oil derrick and wouldn’t allow workers to use levels.

Working on Anderson’s 2007 epic, “There Will Be Blood” (screening Aug. 25), Fisk found blueprints for an actual turn-of-the-20th-century oil derrick, at over 100 feet, and insisted on old-fashioned building techniques to make it look accurately misshapen. He didn’t even allow the set builders to use levels.

Fisk got his start doing whatever jobs he could find in construction on movie sets, eventually serving as art director — the distinction between that role and production designer is sometimes vague — on films like Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz’s 1973 stylish thriller “Messiah of Evil” (Aug. 11), which counterintuitively fits the PD’s ultrarealistic esthetic to a tee.

“It’s the idea of America as this weird, liminal transitory space where you’re moving through gas stations or supermarkets,” Nayman says. Each space carries a dreamlike quality, which “gets realized through the tactile, material, built reality of what Fisk does.”

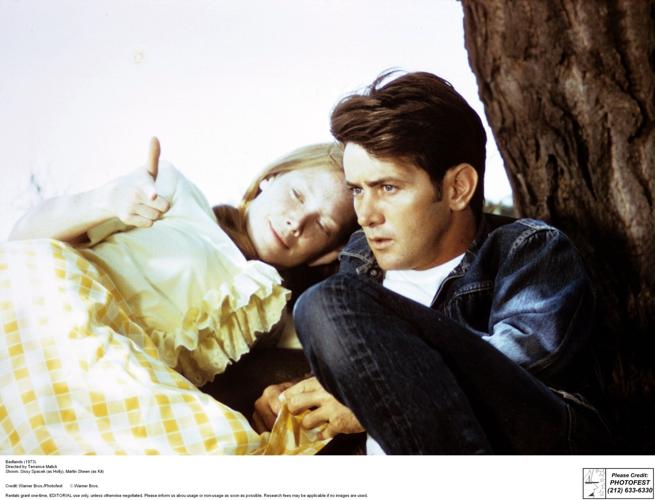

Jack Fisk met his wife Sissy Spacek, as Carrie White in “Carrie,” on the set of “Badlands.”

Fisk later worked on Brian De Palma’s 1976 Stephen King adaptation, “Carrie” (Aug. 17 and Aug. 27). Memorable for its blood-drenched image of star Sissy Spacek, the film wouldn’t have worked without the magically real sets Fisk designed. The prom set, in particular, looks exactly how a ’70s high school prom would, but as Nayman says, “It takes on this enchanted quality. It becomes the staging ground for that apocalypse.”

Fisk also designed Malick’s first film, 1973’s “Badlands” (Aug. 25), bringing to life a nostalgia-tinged, but viscerally real, ’50s-era American Northwest. It’s also where he met Spacek, his wife of 50 years.

Jack Fisk first collaborated with Terrence Malick on 1973’s “Badlands,” starring Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen.

Warner Bros./PhotofestIn the ’80s and early-’90s, Fisk directed four features, two of which starred Spacek, including his 1981 debut, “Raggedy Man” (Aug. 16). Set in Texas during the Second World War, it tells the story of a single mother, a switchboard operator, whose position in her small town is threatened when she strikes up a romance with a sailor (Eric Roberts). Fisk, unfulfilled by the added responsibilities of directing, eventually went back to set-building, but “Raggedy Man” offers further insight into his interests in a rough-hewn, still-developing America.

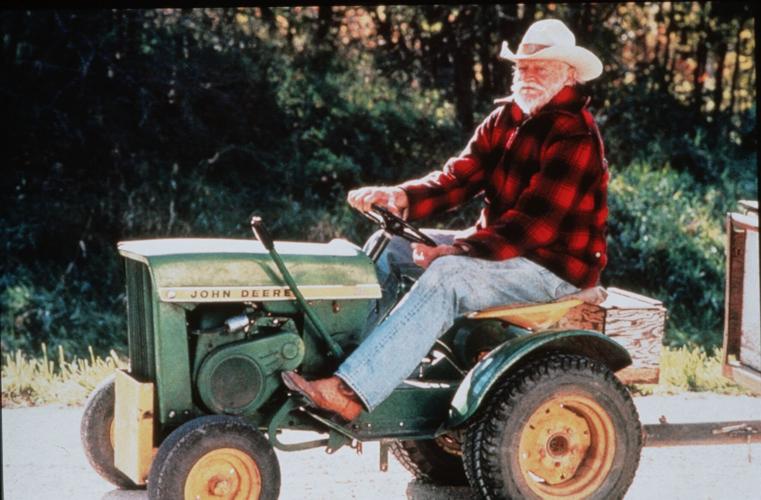

Jack Fisk collaborated with college friend David Lynch on a number of films, including “The Straight Story,” starring Richard Farnsworth.

Lynch, another of Fisk’s great collaborators, has been a friend since high school. The two lived together in Philadelphia during their art school years, sharing an interest in painting. Fisk designed the sets of both 1999’s “The Straight Story” (Aug. 17) and 2001’s “Mulholland Drive” (Aug. 23), movies that feel like polar opposites in Lynch’s filmography, but find unity in their off-kilter views of American mythologies — one earnestly rural, the other seedily Hollywood, and each a home to pained dreamers. Both gain style and texture through Fisk’s work.

“If you believe in the aura around things, or if you believe that realism is a real quality that can be captured by artists,” Nayman says, “the fact that Fisk makes all that stuff the way he does, that kind of comes through.“

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation