GODERICH, Ont.—For years, celebrated Canadian author Alice Munro and her family lived with the secret knowledge that her husband, Gerry Fremlin, molested her daughter when she was a child.

Then came a knock on the door in late 2004.

The Ontario Provincial Police detective was invited into the white cottage-style home in Clinton, Ont. Inside, he informed the couple that he intended to charge Fremlin with sexually abusing Munro’s youngest daughter, Andrea Skinner.

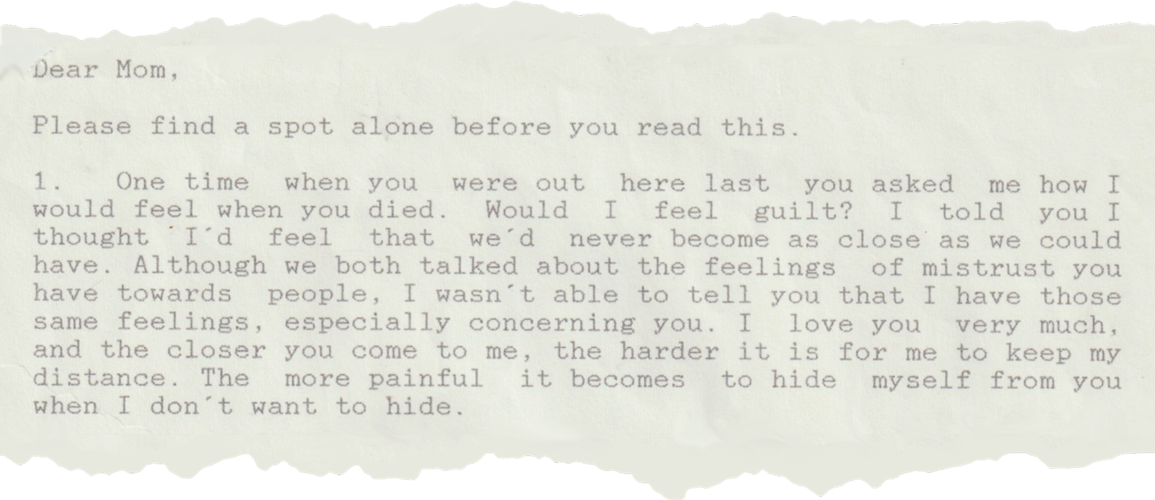

Thirteen years earlier, Skinner had written a letter to her mother describing how Fremlin had molested her in an upstairs bedroom of the home where the author now stood alongside her 80-year-old husband, facing the detective.

Fremlin “didn’t say a word and just kind of stood there,” retired OPP detective Sam Lazarevich said.

Munro exploded.

She went “sideways, totally against her daughter, and all pro for him,” Lazarevich recalled this week. Munro was “yelling, she was mad,” accused her daughter of lying and called her names, he said.

- Andrea Robin Skinner

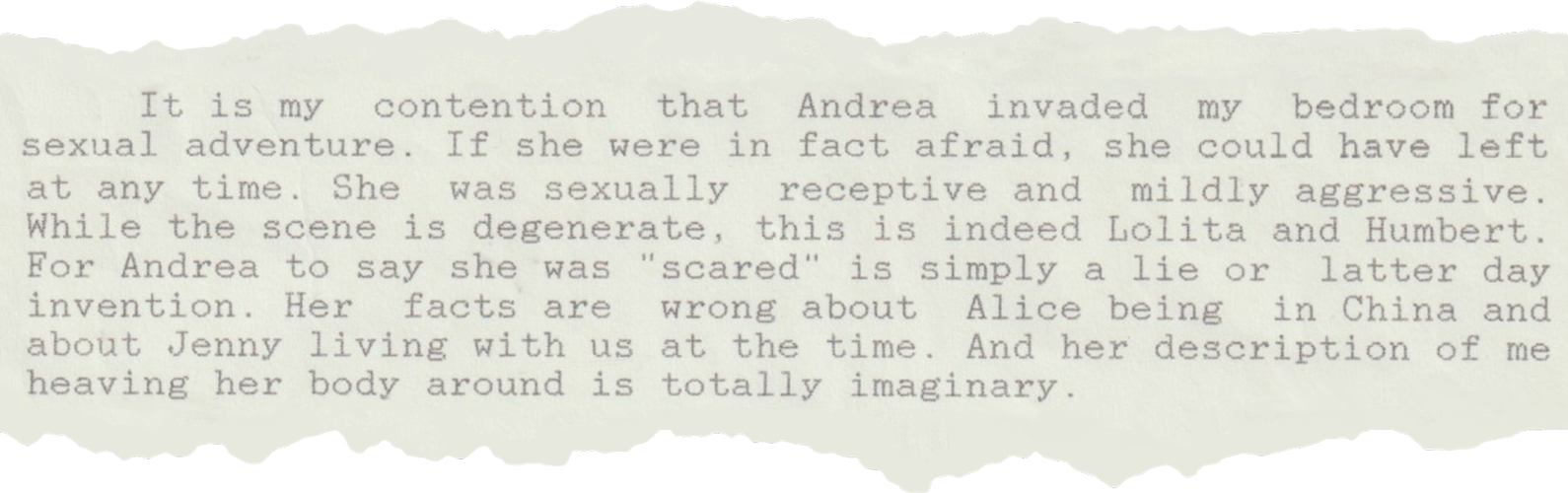

Earlier this month, the Star published Skinner’s account of Fremlin’s sexual abuse, which began in 1976. After she disclosed the abuse to her mother in a letter in 1992, when she was 25, Fremlin responded with letters of his own, admitting to sexual touching but claiming Skinner initiated it — when she was nine.

In 2004, Skinner turned those letters over to police, leading to Lazarevich’s investigation and Fremlin’s quick guilty plea.

The revelation that Munro, whose stories often explored complex mother-daughter relationships, had dismissed the experiences of her own daughter in favour of her abuser has made international headlines and sent shock waves through literary circles, with many asking how they can read the Nobel laureate the same way again.

After receiving her daughter’s letter, Munro briefly separated from her husband but reconciled and remained with him until his death in 2013. Munro married Fremlin in 1976 after her marriage to Skinner’s father ended in divorce. The author died in May, at 92.

After enduring decades of silence, Skinner reported Fremlin’s sexual abuse to police in the fall of 2004 after reading a New York Times interview with her mother. In it, Munro described Fremlin in loving terms and said she had a close relationship with her three daughters — which was a lie. Skinner had severed ties after her twins were born in 2002 and Munro blanched at a request that Fremlin have no contact with the children.

Lazarevich, who retired from the OPP in 2007 after 31 years, was a detective assigned to the Goderich detachment’s major case unit when Skinner’s complaint landed on his desk. Lazarevich drove to interview Skinner at her home then north of Toronto. He had never heard of Fremlin, but he knew who her mother was.

“Whether you read or don’t read, you’ve heard of Alice Munro, that’s a given,” Lazarevich said, sitting in a Tim Hortons in this bustling lakeside town in Huron County — the setting for many of the Nobel Prize winner’s acclaimed short stories. Despite retiring in 2007, Lazarevich leads a busy life as a private investigator and process server, and was — just this week — filling in for a friend at the Walmart located in the same parking lot as the Tim’s.

An excerpt from Andrea’s letter to her mother.

At the time Lazarevich took Skinner’s statement, he was a seasoned detective who had investigated scores of sex-related crimes. Skinner provided him with a candid account, rich in detail. She also showed him the letters Fremlin had written incriminating himself, claiming the nine-year-old had found him, then in his 50s, somehow sexually alluring.

What did Lazarevich think?

“That the guy was a nut,” he said. “A lot of guys like him, they don’t write letters — in fact, he’s the only guy I came across who wrote letters. Mostly the guys just say, ‘She threw herself at me.’ ”

Sex-related crimes can be challenging to prove, which is why investigators “always look for peripheral details,” such as whether the victim told others, Lazarevich explained.

An excerpt from Gerry Fremlin’s response to Andrea’s letter to her mother.

Because Skinner had told her siblings about the abuse, Lazarevich reached out to them and they were on her side, he recalled.

Ultimately, it was Skinner’s credibility, and Fremlin’s typewritten letters, that led Lazarevich to conclude he had grounds to charge Fremlin with indecent assault on Dec. 30, 2004. (Indecent assault is an offence that was law in the 1970s and is equivalent to modern sexual assault.)

“I firmly believed it happened the way she described it,” he said.

After that visit to the couple’s house in Clinton, Ont., Lazarevich remembers shaking his head about Munro’s reaction.

“I couldn’t wrap my head around her attitude,” he said. “If I would have had one of Alice’s books at home, I would have … in the trash can,” he said — demonstrating a gesture of tossing a book into a garbage can.

“From that point on, until she passed away, she’d be getting different awards and honours, and it always bugged me. It bugged me for years.”

Told by the Star about Lazarevich’s recollections, Skinner declined to comment Thursday.

Lazarevich said he is foggy on the details of the actual arrest. He believes Fremlin turned himself in at the OPP Goderich detachment, where he would have been fingerprinted and photographed; Fremlin declined to give a statement to police.

According to documents filed at the Goderich courthouse, Fremlin was released on a promise to appear in court on Feb. 21, 2005.

Fremlin retained family friends Paul and Heather Ross, a married couple and prominent Huron County lawyers, as legal counsel. Paul Ross died earlier this year. Heather Ross, who worked with Munro in the late 1970s to stop a Kingsbridge Catholic Women’s League campaign to ban the books “The Diviners,” “Of Mice and Men” and “Catcher in the Rye,” has retired from practising law.

In a 2020 CBC profile, Heather Ross called Munro “our national treasure.” The couple’s son, lawyer Quinn Ross, said earlier this week the Ross Law Firm cannot confirm Fremlin was a client and is not in a position to comment.

Bob Morris, who in 2005 was a Crown attorney at the historic Goderich courthouse, was assigned to the case.

He recalled it proceeded through the system “very fast.” Morris, 72, retired as a prosecutor after 32 years and now works in Goderich as a defence lawyer.

Andrea, photographed in Port Hope this month.

Steve Russell Toronto StarMorris recalled a meeting with Paul Ross to discuss potential resolutions. He believes the defence lawyer likely inquired whether his elderly client could be granted a non-custodial sentence, with certain safeguards, if he entered a guilty plea. Morris said he would have consulted with Skinner to explain that a trial could result in a harsher sentence, but with no certainties on the outcome.

On March 11, 2005, Fremlin pleaded guilty before Justice John Kennedy, who gave him a suspended sentence and two years probation with conditions not to have contact with Skinner, and not to be in the company of a person under 16 unless accompanied by an adult.

Skinner was not in court to hear her abuser admit what he had done, although she provided a victim impact statement, which she has asked to remain private.

Also not in court were any media representatives; news of Fremlin’s plea went unreported until last weekend — despite Skinner’s efforts over the years to bring it to public attention.

Lazarevich this week recalled Skinner’s concerns about people doubting her story. So, after Fremlin pleaded guilty, he “got a hold of Andrea and said, ‘Look, he didn’t deny in court, he didn’t ask for a trial to fight it, he pled guilty. What does that say about you? It says that you’re believable.’ ”

Reflecting on Munro’s reaction that day, Lazarevich said it’s far from the first time he’s encountered parents who ignore sexual abuse for “whatever reason,” be it love, fear, dependency or the belief they can “just try and make sure that she’s not home by herself, or try and make sure I’m always around.”

After his decades in the criminal justice system, Morris has also seen many cases like this where “families have hidden secrets.”

He hopes Skinner’s disclosure and the ensuing media coverage are a positive development, “in a sense that it shines the light on abuse that was hidden and often continues because no one ever exposes it. So, in that sense, I think it’s good so in the future people, perhaps predators, might realize that they shouldn’t be doing what they’re doing and there are consequences.”

Correction — July 12, 2024

In the 1970s, Heather Ross worked with author Alice Munro to stop a Kingsbridge Catholic Women’s League campaign to ban the books “The Diviners,” “Of Mice and Men” and “Catcher in the Rye.” A previous version of this article mistakenly said Ross worked with Munro to stop three of Munro’s books from being banned in Huron County.