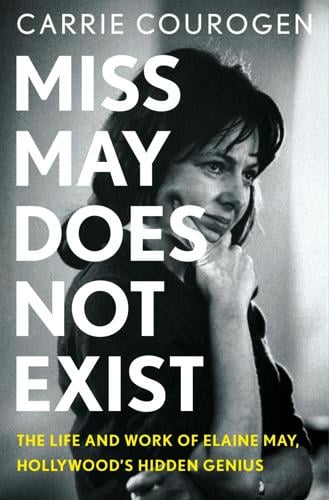

The title of Carrie Courogen’s new biography of the legendary comedian and filmmaker Elaine May draws a bead on its subject’s uniquely elusive and ephemeral sense of humour: it’s called “Miss May Does Not Exist.”

That May, who just turned 92, has spent much of her career on the sidelines is undeniable. Despite being universally respected by multiple generations of joke-slingers, she has a body of work as a director that’s defined by its scarcity: just four features, and none after the notorious 1987 flop “Ishtar.”

Since the 1980s, she’s worked most steadily as an in-demand (and self-effacing) studio script doctor, punching up tepid material with a mix of loopy non sequiturs and precise wisecracks. She’s a genius who lives on the margins: the question is whether she was relegated there by a timorous and misogynistic Hollywood establishment, or else sought refuge of her own volition.

The answer, as elucidated in Courogen’s book, is, naturally, a bit of both. The same mercurial, fast-twitch brilliance that made May a rising mainstream star in the 1960s, devising and performing brainy, zany routines with her (professional) partner Mike Nichols — a tag team that casually rewrote the rules of sketch comedy — left industry power brokers variously intimidated and nonplussed.

In her new biography of Elaine May, Carrie Courogen draws a bead on its subject’s uniquely elusive and ephemeral sense of humour.

St. Martin’s PressThat May insisted on a very particular (and not especially cost-effective) way of moviemaking earned her a reputation as a kind of cinematic kamikaze pilot — one willing to crash and burn on her own terms.

While shooting 1975’s “Mikey and Nicky” — a scabrously funny two-hander about a couple of Philadelphia low-lifes clinging to each other during a dark night of the soul — she famously upbraided her cameraman for putting his equipment down after the actors had literally improvised their way out of the frame and closed the door behind them: “They might come back!” she pleaded.

“Mikey and Nicky” is included in “Directed by Elaine May: A Feral Filmography,” the Revue Cinema’s new August series dedicated to May, which has been programmed by stalwart critic and historian Alicia Fletcher (in an email, Fletcher promised that the screenings will feature original May-themed merchandise). After leaving critics mostly bewildered on its initial release, “Mikey and Nicky” has subsequently been canonized as a masterpiece of the New Hollywood on par with the films of its co-star John Cassavetes, whose performance plumbs murky, bottomless depths of self-loathing.

What May and Cassavetes had in common was an affection for messy (and messed-up) characters, as well as for stories that did end runs around genre clichés: they refused to make things easy on themselves, or on their audiences. Take May’s 1971 debut feature, “A New Leaf,” which has a plot right out of a 1940s screwball comedy — a destitute playboy (Walter Matthau) tries to marry himself back into prosperity — but it’s filtered through a murderous misanthropy closer to Alfred Hitchcock. The story goes that Paramount chief Robert Evans took the movie away from May in order to excise the excess bad vibes, effectively mutilating a potential all-time classic.

May herself starred in “A New Leaf,” and her performance as the socially inept heiress Henrietta Lowell perfectly inverts the preening narcissism of the era’s A-list matinee idol turned auteurs. While Robert Redford and Warren Beatty effectively flattered themselves onscreen after stepping behind the camera, May turned herself into the movie’s punchline. (She also boldly cast her daughter, Jeannie Berlin, in a borderline-abject role in 1972’s “The Heartbreak Kid.”)

May’s friendship with Beatty — who counted himself as a fan of her work — would ultimately lead to the cataclysmic production of “Ishtar,” which, like “A New Leaf,” was essentially a throwback, this time to the goofy, crowd-pleasing buddy pictures that sent Bob Hope and Bing Crosby off to riff in exotic locales. May’s chosen duo was Beatty and Dustin Hoffman, cast as off-brand Simon and Garfunkel manqués waylaid in war-torn Morocco. For reasons both within and beyond her control, the film went dangerously overbudget en route to becoming a late-’80s metonym for box-office failure. “If all the people who hate ‘Ishtar’ had seen it,” May quipped, “I would be a rich woman today.”

Viewed nearly 40 years later, “Ishtar” isn’t hateable at all. Rather, it’s an imperfect and intermittently ingenious political satire that deftly crosses the streams between the American military- and entertainment-industrial complexes. (In an era of Reaganite triumphalism at the multiplex, its skepticism about U.S. foreign policy and the role of the CIA in international regime change was welcome.)

Its failure meant the end of May’s career as a director — a telling detail considering that nearly every one of her male contemporaries (including Beatty and Nichols) managed to rebound and rebuild their reputations after comparable commercial debacles. Earlier this year, it was reported that May was developing a new film, tentatively titled “Crackpot,” starring Dakota Johnson, whose interviews during the “Madame Web” junkets suggested that she was a lot more enthusiastic about the prospect of working with May than promoting “Madame Web.”

Time will tell whether the project will actually be completed, but it’s nevertheless nice to think (or hope) that there will eventually be one more Elaine May movie.

To join the conversation set a first and last name in your user profile.

Sign in or register for free to join the Conversation